This is an excerpt from The CEO’s Guide to the Investment Galaxy: Navigating Markets to Build Great Companies by Sarah Williamson.

Let’s say you lead a young company. You’ve built a team, created an in-demand product or service, and you’re considering going public.

There are lots of benefits to being a public company, but there are costs, too. The goal is to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs.

The first benefit of being a public company is access to large pools of capital. Being listed opens up the equity market to fund you in an IPO but also puts you on the radar for other types of capital, such as follow-on offerings of equity, convertible bonds, and all sorts of structures that trade in the public markets. This new capital could fuel your next stage of growth by allowing you to invest in the R&D, talent, and technology you need to grow. It also allows you to issue stock in the future if you want to acquire another company.

The second benefit is more subtle: public markets impose discipline and confer credibility; they make you grow up. The rules, regulations, and independent board members that public markets require mean that there is a framework for doing things that goes beyond the founder’s or leader’s vision and quirks. With a few notable exceptions, public companies behave in a more deliberate and predictable way than pre-IPO companies. And there is prestige to being a public company, making you more visible to potential customers and employees.

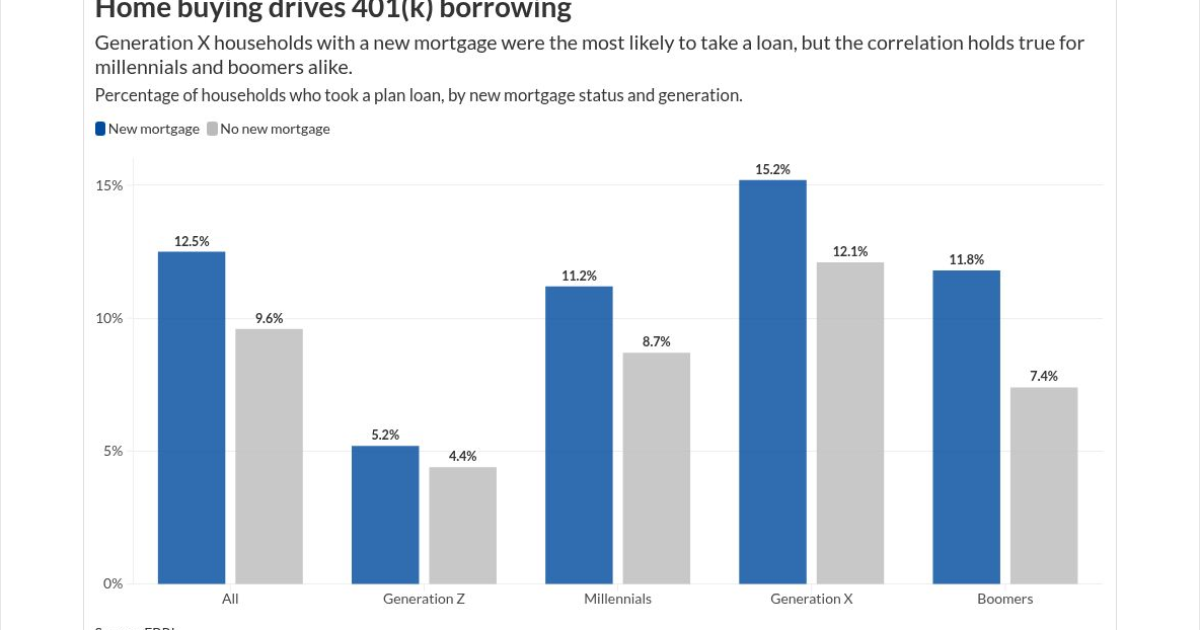

The third benefit is liquidity for you and your employees. Perhaps you started this company years ago and while the equity value has grown, you and your employees have little cash. Maybe it is time to buy houses, diversify wealth, or take a well-earned vacation. Liquidity is an important consideration for going public, but going public isn’t a cash-out event if you’re building a long-term company. As an extreme example, when Amazon went public in 1997, it sold 3 million shares and raised $54 million, leading to a market cap of $438 million. Jeff Bezos retained a 43% stake in the company, a far cry from cashing out. The rest is history.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; false;clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width: 600px;}

/* Add your own Mailchimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Sign Up for The Start Newsletter

(function($) {window.fnames = new Array(); window.ftypes = new Array();fnames[0]=’EMAIL’;ftypes[0]=’email’;fnames[1]=’FNAME’;ftypes[1]=’text’;fnames[2]=’LNAME’;ftypes[2]=’text’;fnames[3]=’ADDRESS’;ftypes[3]=’address’;fnames[4]=’PHONE’;ftypes[4]=’phone’;fnames[5]=’MMERGE5′;ftypes[5]=’text’;}(jQuery));var $mcj = jQuery.noConflict(true);

Of course, going public has costs too. You have to deal with all those pesky inhabitants of the investment galaxy that we met earlier. The first cost is that you have to follow the rules. While rules impose discipline, they also impose costs and constraints. Reporting, disclosure, and even board minutes become really important.

The second is that going public is expensive. The advisors that will take you public are experts that expect to get paid and paid handsomely. While there are ways around this (like a Dutch auction or a direct listing), the traditional IPO comes with a hefty price tag.

The third is that you need to change or add to your board. Good public company boards are a strategic asset of the corporation. The board members represent the public shareholder and the long-term vision of the company, not their own pocketbook. A strong board that can provide guidance to a public company is likely different from the board you have right now. A well-known business book by Marshall Goldsmith is entitled What Got You Here Won’t Get You There—and this applies to boards too.

Some early board members can switch their perspective to become excellent long-term public company board members, but others may continue to see themselves as VCs looking for their next deal. Be sure you have the right mix, ideally well before the IPO.

Finally, you need to change the way you think about your shareholders and how you deal with them. Your pre-IPO shareholders are probably insiders, part of your team: employees, a few VCs, friends, and family. But now that you’re moving into the rough and tumble world of public markets, you will find yourself with a different mix. Starting out with the right share- holders will make your life much better over time. Getting the right share- holders, however, is hard work.

The way IPOs traditionally work is that a group of investment banks underwrites the company, usually with one in the lead left role. They do the work to prep the financials and the management team for the scrutiny of the public market. They may work with you to ensure your board is ready for the public markets. Their analysts will write about your company’s prospects, and their bankers will take the management team on a road show, introducing you and your team to a range of investors that you probably don’t know.

By underwriting your company, the investment banks put their stamp of approval on you and your strategy. And then they price the IPO— making an intelligent guess based on their market knowledge of the demand for your company’s stock.

Pricing an IPO properly is hard. Bankers pricing an IPO must navigate between leaving too much money on the table if they price it too low or watching the stock flounder on its first day of trading if they price it too high.

Usually, they price the IPO on the low side. People like stocks to rise rather than fall in the first few days of trading: it feels good to have an IPO pop. And if the price starts to fall, the banks will typically step in to support it, which they don’t want to do.

But remember that if you price something too low, and the value goes up right away, you’ve probably left money on the table. The key long-term issue is who gets what allocations. Historically, investment banks have allocated IPO shares to their best clients.

If an investor buys shares and can sell them shortly thereafter for well above their purchase price, they’ll be very happy with that bank. Of course, investment banks want to make their best clients happy. But their best clients may not be your best shareholders in the long term.

Remember that the best clients of the sell-side are those that trade the most, either because they are large or because they turn over their portfolios constantly. Those investors may or may not be who you’re looking to add to your shareholder roster.

The more shares allocated to short-term investors who simply want to earn the pop and flip them, the less value accrues to the kind of long-term shareholders you need to support your company in its new phase. You will have failed to build a shareholder roster that will stick with you over the long term. You and your investment bank both want a successful IPO, but you have different incentives and time frames.

There are several steps you can take to set up your young company for long-term success. These steps include building strong governance, aligning your incentives, having a clear investor strategy, and avoiding quarterly guidance. While entering the public markets will require you to change the way you do some things, it does not mean becoming short-term oriented, as the examples of Alphabet and Amazon show.

Key Planets on This Journey

The key planets in the investment universe that a young company going public should focus on are:

Investment bankers. Who takes you public can influence your prospects long after your shares start trading. Selecting the right banker, one that knows your industry well and wants to set you up for long-term success, is critical. You will end up paying the bankers a lot, so be sure the team is working for you and your interests.

Regulators, exchanges, and lawyers. These will matter in ways they never did before. Going public is an important decision that brings scrutiny and risk as well as opportunity. You need to understand the rules of the new game you’re playing and take care not to violate them.

Active managers. Do your own homework on what investors you would like to have for the long term and focus on them—not the flippers. Most likely, these are the active managers we met above. There may be some boutiques you would like to have on your roster as well, but don’t let the bankers take you blindly on a roadshow. Build credibility and relationships with your target shareholders. Check the allocations and be sure those long-term investors are getting their fair share.

Going public is an exciting and critical time in your company’s life. A successful IPO can provide you with the fuel you need to get your company to the next stage of the journey. But remember it is not the destination.

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, Wiley, from The CEO’s Guide to the Investment Galaxy: Navigating Markets to Build Great Companies by Sarah Keohane Williamson. Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

The post IPO or Bust? How to Build the Right Shareholder Roster Before You Go Public. appeared first on StartupNation.