Everyone’s getting terribly excited about robots these days. I’m finishing the research for a new report on embodied or physical AI, which explores how the careful addition of AI can make a new generation of robots more flexible, adaptable, and cost-effective than their predominantly rules-based predecessors.

Instead of just doing one task well, over and over again, embodied AI helps robots adapt to changes in their operating environment, and even variations to the task itself.

At events in the past couple of weeks, two software vendors both explicitly addressed a critical piece that’s missing from most conversations about this trend: connecting these increasingly capable robot workers to workflows designed around human workers.

Assume That Tasks Will Be Completed By Human, Digital, Or Robot Workers

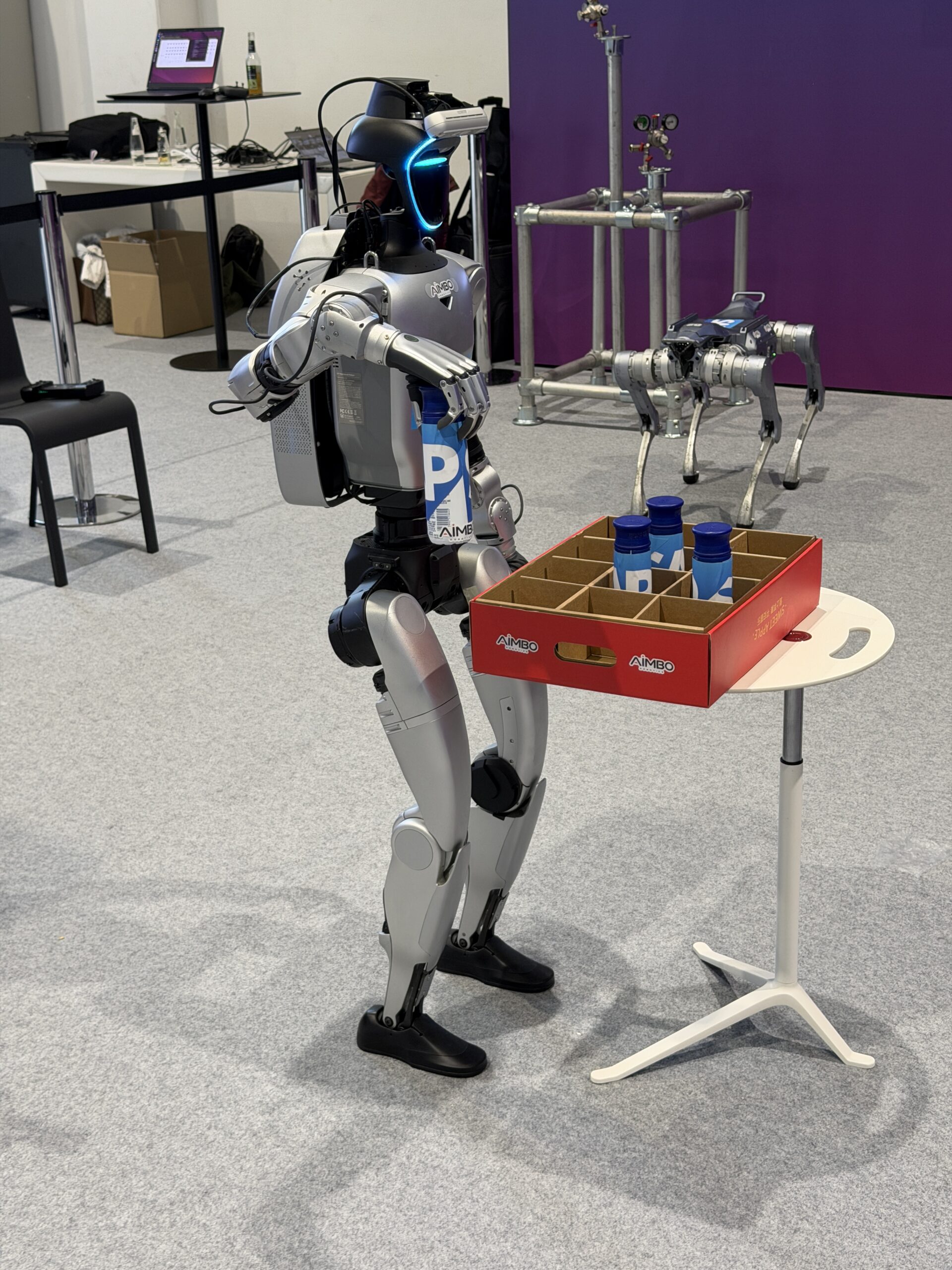

Earlier this month, in Berlin, SAP announced partnerships with a number of robotics firms, and showed early pilots and proofs of concept with shared customers like automotive supplier Martur Fompak or refrigeration company Bitzer. Despite the SAP logos plastered across every robot wandering Berlin Messe’s halls, the software company isn’t claiming to build or deploy robots. Instead, SAP is working on the integration between those robots and the systems over which it does have control: solutions like SAP business technology platform (BTP), or extended warehouse management (EWM). In essence, SAP is helping robot deployments to scale beyond today’s pilots and proofs of concept, integrating the process by which customers tell their robots what to do into the proven enterprise-grade workflows that already track the movement of goods and people through factories and warehouses around the world. In demonstrations at the event pilot customers used SAP’s AI chatbot – Joule – to ask a robot to fetch a part or inspect a component, logging results back into SAP’s systems of record.

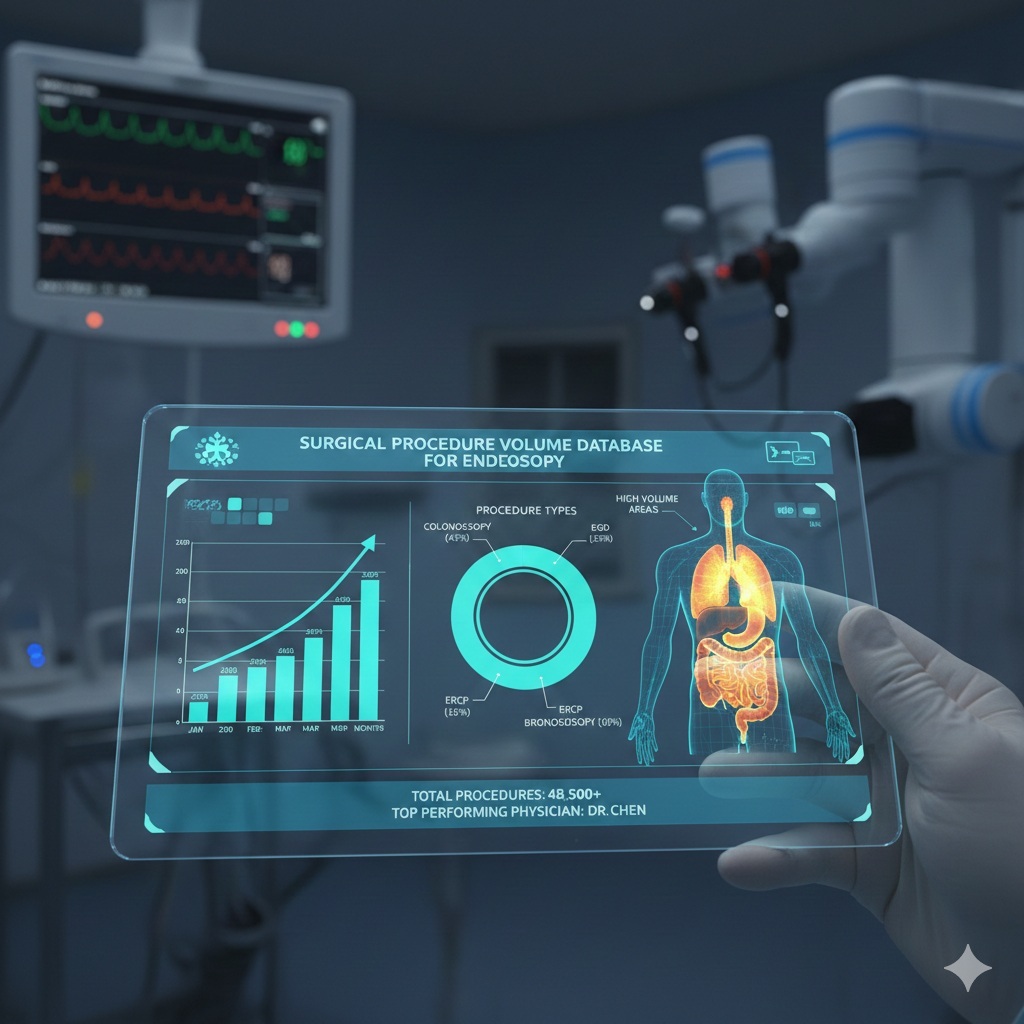

Last week, in New York, IFS told a broadly similar story and announced its own set of partnerships with firms like Boston Dynamics and 1X. I’m not in a position to comment on the relative strengths of these capabilities yet, but I can say that IFS did a better job of clearly communicating the art of the possible. From CEO Mark Moffat’s opening keynote to deep dives from chief product officer Christian Pedersen and others, the message was consistent and crystal-clear: there will be (and, increasingly, already are) human workers, digital workers (AI agents), and robotic workers, and enterprise tools like IFS’ need to make it straightforward for customers to identify and task the right worker for each job.

Instead of managing people, agents, and robots separately, customers should be able to pick the right tool for the job. In a series of demos that connected the pieces of their story, the IFS team showed their software helping an imaginary maker of industrial packaging machines to support a field service use case: human support agents, human field service engineers, AI agents, and a Boston Dynamics robotic dog worked together to identify, triage, and resolve a problem before it led to expensive unexpected downtime. Real customers helped to flesh out the story, showing their journey towards really implementing pieces of the whole.

And, probably coincidentally, a contact at Siemens also drew my attention to a short video last week which shows how their Process Simulate tool is able to simulate the integration of humanoid robots into existing industrial workflows. This is not quite the same as the pitches from IFS or SAP, but it’s clearly part of a broader trend towards embedding robots more tightly into normal operations on and around the factory floor.

The Shift From Pilot To Production Is Not Just About Better Robots

Robots are getting better and more capable. Advances in the physical robot and advances in its brain (the embodied AI bit which my new report will explore) are truly remarkable. But neither is enough if we want to escape robotic pilot purgatory. If you have one of Boston Dynamics’ Spot dogs (or an Anybotics ANYmal, or one of the relatively affordable Unitree G1 humanoids that so many of my manufacturing clients are so excited to acquire and then show off), then it’s entirely understandable that you treat it as special.

You nurture it, you take care of it, you accept its quirks, and you fully expect to manage it outside the workflows and processes by which you manage everything else. For one robot, that’s fine. It might even be fine for 10, or 20. For 100, or 200, or 200,000, it’s entirely unacceptable, and that’s the future towards which IFS and SAP are pointing. Yes, it’s sort of fun to instruct a robot by chatting with SAP’s Joule chatbot, but there are plenty of other ways to tell a single robot what to do. Voice commands, and imitation learning scenarios in which it watches and copies what you do are equally fun, equally effective, and equally divorced from the reality of consistently and cost-effectively managing large cohorts of workers.

In my earlier work around Forrester’s automation triangle, I explored the need to balance physical automation (robots), software automation (AI agents, increasingly), and the human workforce. Both IFS and SAP are pointing towards a near-term future in which the businesses that depend on these three types of worker will have the tools to play to their strengths, at scale.

As always, if you have solutions or stories of your own to share, please schedule a Briefing and tell me all about them. If you’re a client who wants to dig more deeply into any of these ideas, please schedule an Inquiry or Guidance Session.