Scroll through social media and you’ll find financial advice delivered with absolute certainty: car payments are bad, debt is always a mistake, save aggressively now, enjoy that cash later. The problem isn’t that this advice is inherently wrong — it’s that it’s rarely personal. Financial decisions aren’t binary; they happen in the context of individual preferences, risk tolerance, time horizons, and — crucially — how much value someone places on enjoying life today versus tomorrow.

Utility Isn’t Universal

In economics, utility refers to the satisfaction someone derives from consumption. Two people can spend the same amount of money and experience vastly different benefits. Take car financing. Online advice often treats car payments as a sin. But if someone gains significant daily value from a reliable, comfortable car — for commuting, a growing family, or personal enjoyment — financing that car may be a rational choice. Waiting years to save and buy outright may be “optimal” on paper, but it comes at the trade-off of not having access to that utility today.

The Opportunity Cost of Everything

Every financial decision has an opportunity cost — including saving. Investing money today is a choice not to spend it. Much advice assumes that foregone consumption is painless. For many people, it isn’t. The question isn’t “Is it better to invest or spend?” It’s “What am I giving up, and is it worth it?” Hyper-frugality taken to its extreme — the beans-and-rice diet for decades — is hardly a fulfilling way to live, yet it underpins much online financial commentary.

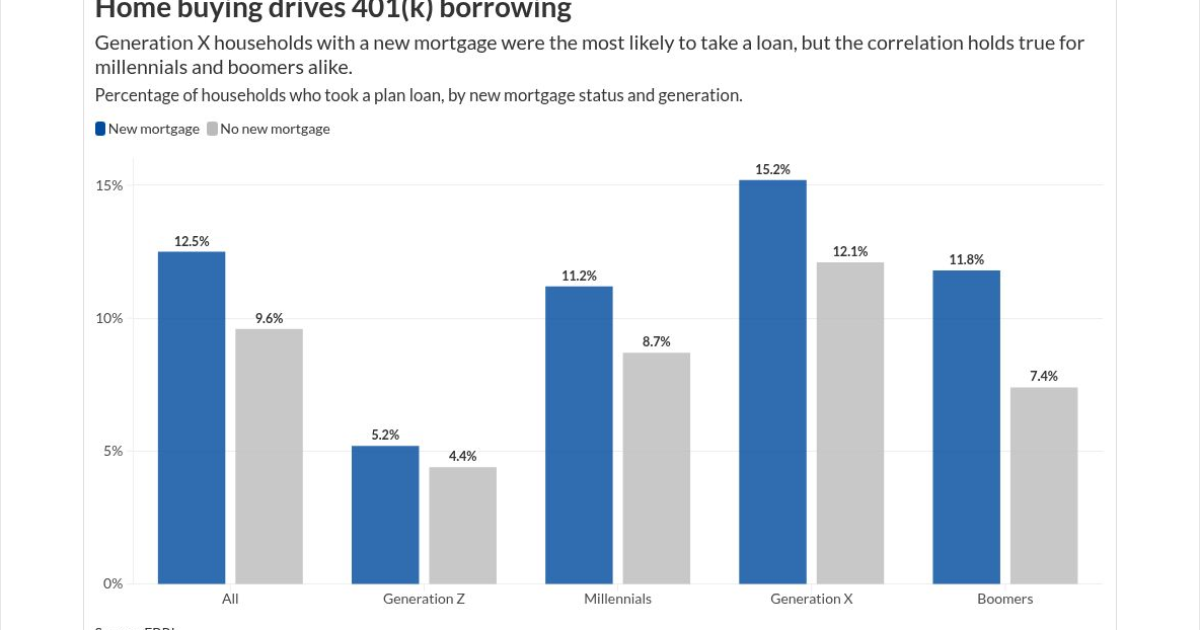

The Reality of Market Volatility

Even conventional wisdom — investing in an equity index — can be deeply uncomfortable in practice. From 2000 to 2009, a $10,000 lump sum invested in the generated approximately a –9.1% net return. Investing $1,000 in discrete amounts at the beginning of each year over the same period produced a cumulative return of roughly 5.2% — hardly anything to write home about. It’s difficult even for experienced investors to stick with a strategy after suffering an almost 40% drawdown within the first few years — never mind the average person simply trying to build some financial security. Professional investment committees would have their competence questioned after such outcomes. Compounding only works if investors can endure long periods of stagnation or loss. Recognising this discomfort is just as important as recognising the trade-offs involved in debt or consumption decisions. Personal preferences shape tolerance for market volatility. What is theoretically optimal may be psychologically intolerable in practice.

Source: YCharts, S&P 500 Total Return Index, 2000–2009. Chart shows the growth of $10,000 invested from the beginning of 2000 to the end of 2009.

Even Companies Use Debt — Constantly

Corporations borrow routinely, even highly profitable ones, to fund growth and smooth cash flows. or are not criticised for issuing debt despite holding substantial cash reserves. Households aren’t corporations, but blanket statements that all personal debt is bad miss important nuance. Debt, when used deliberately and sustainably, can be a tool — not a moral failing. The real problem is misaligned debt: borrowing without understanding the cost, risk, or long-term impact on financial flexibility.

Not Everyone Wants to Be an Investor

Not everyone finds satisfaction in watching their portfolio swing up and down day to day. Some people place greater value on experiences, comfort, or time. Others prioritise security or optionality over maximising returns. None of these preferences are wrong. Personal finance isn’t about turning everyone into a mini hedge fund manager; it’s about aligning financial choices with personal goals, values, and constraints.

The Uncomfortable Truth: Tomorrow Isn’t Guaranteed

Life is uncertain. Planning for the future is sensible, but no one is guaranteed to reach 65 in good health — or at all. That doesn’t justify reckless spending, but it does challenge the idea that deferred consumption is always superior. A balanced financial life acknowledges both the need to prepare for tomorrow and the value of living today.

Context Is Everything

Good financial advice starts by asking the right questions: What do you value? What trade-offs are you comfortable making? There are no universally correct answers — but asking these questions is essential to making rational, informed decisions. Bad advice skips them entirely. Money decisions are deeply personal, shaped by psychology as much as spreadsheets. The smartest financial plan isn’t necessarily the one that looks best online or leaves you with the largest retirement account — it’s the one that fits the life you actually want to live.