Yves here. The article below explains how both advanced and emerging economies can remedy their seemingly intractible problem of high public debt levels and low growth: by properly focusing spending on productivity/output increasing areas, such as infrastructure and health, and increasing efficiency of govenment operations. Note that this analysis immplicity assumes that the countries in this fix are, like Eurozone member states, not monetarily sovereign. But even those that are often have to contend with the objections of budget hawks.

Even Larry Summers, a mainstream economist of only a mildly Keynesian persuasion, stressed that infrastructure spending more than paid for itself (when you have as much backlog and deferred maintenance as the US does), generating GDP growth of as much as 3x the expenditure.

Yet many advanced economies have bought the neoliberal fairy tale that private development and ownership of pubic services such as infrastructre will be more efficient. The fees associated with complex legal strucuting and fundraising for these deals alone makes the idea that they will be cheaper (ex delivering a very inferior product) dubious. A simple proof: in the US, every newly-built public toll road has gone bankrupt. As we wrote in 2021:

One obvious form of grifting is toll roads. A 2014 article on privatizations, describing the economics of new toll road projects, explains how they always go bust. I have seen no evidence that the structure or terms of these deals have changed to favor users and taxpayers. From Thinking Highways:

Beginning with the contracting stage, the evidence suggests toll operating public private partnerships are transportation shell companies for international financiers and contractors who blueprint future bankruptcies. Because Uncle Sam generally guarantees the bonds – by far the largest chunk of “private” money – if and when the private toll road or tunnel partner goes bankrupt, taxpayers are forced to pay off the bonds while absorbing all loans the state and federal governments gave the private shell company and any accumulated depreciation. Yet the shell company’s parent firms get to keep years of actual toll income, on top of millions in design-build cost overruns….

Of course, no executive comes forward and says, “We’re planning to go bankrupt,” but an analysis of the data is shocking. There do not appear to be any American private toll firms still in operation under the same management 15 years after construction closed. The original toll firms seem consistently to have gone bankrupt or “zeroed their assets” and walked away, leaving taxpayers a highway now needing repair and having to pay off the bonds and absorb the loans and the depreciation.

The list of bankrupt firms is staggering, from Virginia’s Pocahontas Parkway to Presidio Parkway in San Francisco to Canada’s “Sea to Sky Highway” to Orange County’s Riverside Freeway to Detroit’s Windsor Tunnel to Brisbane, Australia’s Airport Link to South Carolina’s Connector 2000 to San Diego’s South Bay Expressway to Austin’s Cintra SH 130 to a couple dozen other toll facilities.

We cannot find any American private toll companies, furthermore, meeting their pre-construction traffic projections. Even those shell companies not in bankruptcy court usually produce half the income they projected to bondholders and federal and state officials prior to construction.

Putting aside obvious public burdens like bankruptices, private ownership of infrastructure is inherently a bad deal for citizens. Financiers “sweat the asset” by jacking up charges, like landing fees for airports, and skimping on maintenance.

US healtcare, with its high costs and poor outcomes, is the poster child of what happens with profit incentives in all the wrong places. And now we have the EU and US set to bulk up on similarly overpriced arms spending.

So even if policy makers take proposals like these to heart, they have to overcome a lot of intellectual capture and corruption to get them implemented. And all the signs are that inertia and horrible leadership will guarantee that conditions will get worse, save for those at the top.

PS: Before you pooh pooh this article because its authors work for the IMF, keep in mind that there has long been a split between the research side of house, which has long advocated progressive (in the older sense fo the word) reforms, and the “program” side, which is a hard-nosed neoliberal enforcer.

By Era Dabla-Norris, Deputy Director, Fiscal Affairs Department International Monetary Fund, Davide Furceri, Division Chief, Fiscal Affairs Department International Monetary Fund. Zsuzsa Munkacsi, Economist International Monetary Fund, and Galen Sher, Economist, International Monetary Fund. Originally published at VoxEU

With high public debt and weak medium-term growth, finance ministries seek to do more with less. This column argues that efficiency gaps in public spending stand at about 30-40% globally and are pronounced in infrastructure investment and R&D spending. Using empirical and model-based analysis, it shows that reallocating spending to infrastructure, education, health, and R&D and closing efficiency gaps can raise GDP by 11% in emerging market and developing economies and 4% in advanced economies, over the long term, and crucially without increases in total spending.

Public debt is set to surpass 100% of GDP in the next four years globally, according to the latest IMF projections. Higher interest rates, and pressure to spend more on defence, ageing societies, and development create a constrained environment where every dollar of public money has to work harder in delivering better outcomes. Compounding this challenge, medium-term growth prospects have remained persistently subdued since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The IMF’s October 2025 Fiscal Monitor finds that countries have substantial scope to reallocate public spending to support economic growth, and they could gain around one third more value for money by adopting the practices of best performers (IMF 2025). Moreover, the report finds that spending smarter – through improved composition and increased efficiency – can raise GDP by 11% in emerging market and developing economies and 4% in advanced economies, over the long term.

Scope for Reforms

Public spending as a share of GDP has doubled in advanced and emerging market economies since the 1960s; however, the allocation has not been pro-growth. Globally, public investment as a share of total expenditure has declined by two percentage points, while spending on public education has stagnated at about 11% of total expenditure – less than half of public wage bills.

Critically, our new estimates for 174 countries suggest that nearly all have substantial room to improve the efficiency of public spending. Building on a rich literature (e.g. Apeti et al. 2023, Herrera et al. 2025), we measure the distance of countries from a production possibilities frontier, which represents the best possible outcomes in infrastructure, health, education, and research and development spending. Importantly, our estimates are the first to vary over time while also allowing for structural differences across countries, statistical noise, and uncertainty over the choice of outcome variables.

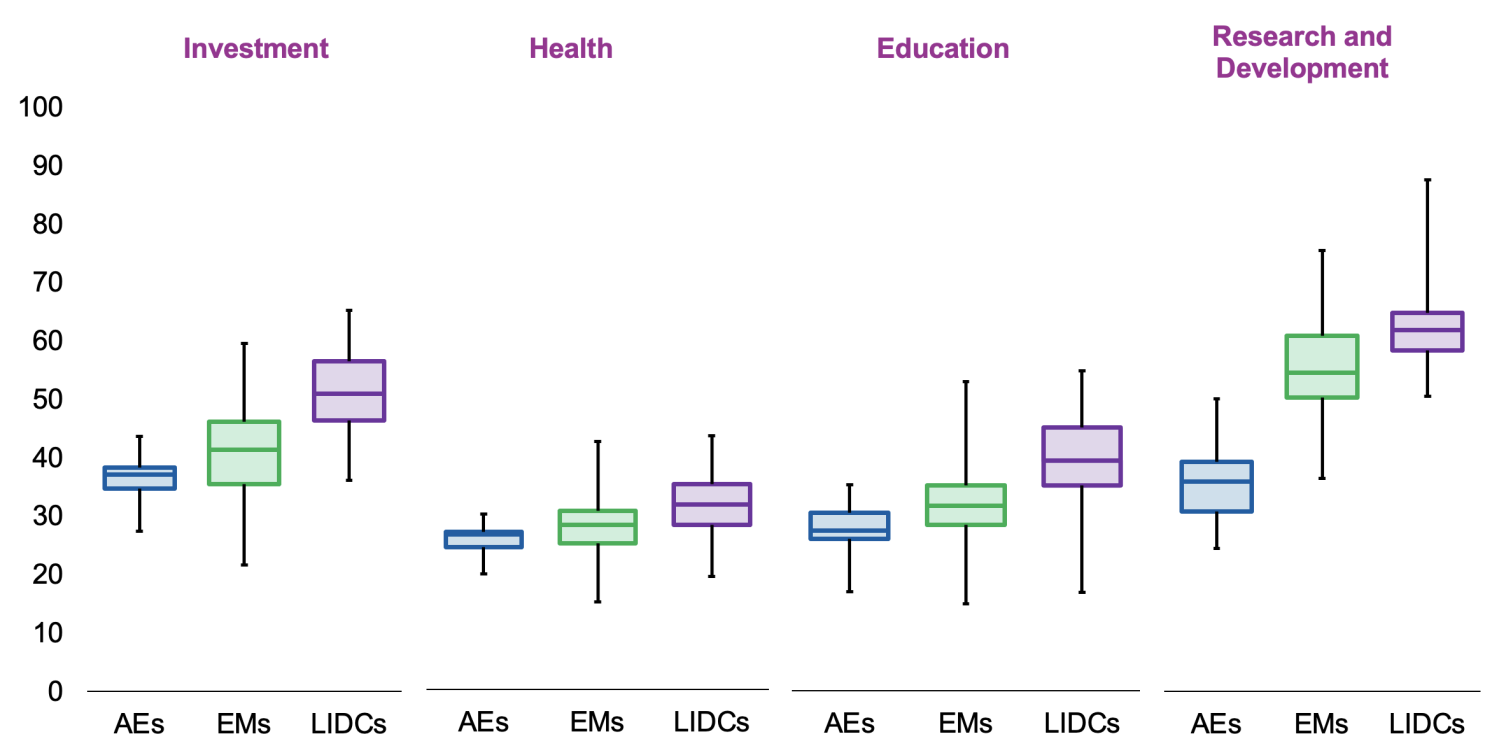

The dataset reveals that efficiency gaps stand at about 30-40% globally today and are pronounced in infrastructure investment and research and development spending (Figure 1). These gaps have narrowed considerably over the past four decades, reflecting worldwide increases in life expectancy, technological advancements, and expanded access to basic infrastructure in low-income developing countries.

Figure 1 Public spending efficiency gaps (percent)

Notes: The figure shows efficiency gaps, which are distances to the spending efficiency frontier. Efficiency gaps range from 0 (fully efficient) to 100 (fully inefficient). The figure shows averages from 1980 to 2023. The boxes indicate medians and interquartile ranges (25th –75th percentiles), and the whiskers delineate the minimum and maximum values. AEs = advanced economies, EMs = emerging market economies, LIDCs = low-income developing countries.

Output Gains from Reforms

A vast literature examines how the allocation and efficiency of public spending contribute to growth. In standard growth models, public investment in physical and human capital increases the economy’s productive capacity, and public R&D spending adds to the knowledge base that firms use to innovate (Barro and Sala-i-Martin 2004). More efficient public investment adds more to the capital stock (Gupta et al. 2014, Presbitero et al. 2016).

We contribute to this literature in two key dimensions. First, we analyse – through both empirical and model-based analysis – how the composition of public spending affects economic activity, assuming total spending remains constant. Second, we assess how the economic effects vary across countries and over time, based on the new estimates of efficiency.

Empirical evidence – using local projection and synthetic control methods – from about 700 episodes of large reallocations in public spending in 155 countries suggests that output increases substantially in the short to medium term. A major reallocation to public investment is followed by an increase in output of about 4% ten years later. Reallocations to public health and R&D spending are followed by 3% increases in output over ten years. These gains start to emerge even in the first five years and increase over time.

Indeed, simulations of an endogenous growth model clearly illustrate the potential long-term gains and the economic mechanism. Public infrastructure adds to output alongside private capital and labour (as in Traum and Yang 2015), while public investment in human capital enhances the productivity of time spent in education, accelerating skill accumulation. Public R&D spending expands the stock of innovations available for firms to adopt, with technology diffusion occurring gradually as firms invest in adoption (as in Anzoategui et al. 2019). The model explicitly incorporates inefficiencies in public investment, human capital, and R&D, by allowing some public spending to be wasted instead of contributing to the stocks of capital and knowledge (as in Berg et al. 2019).

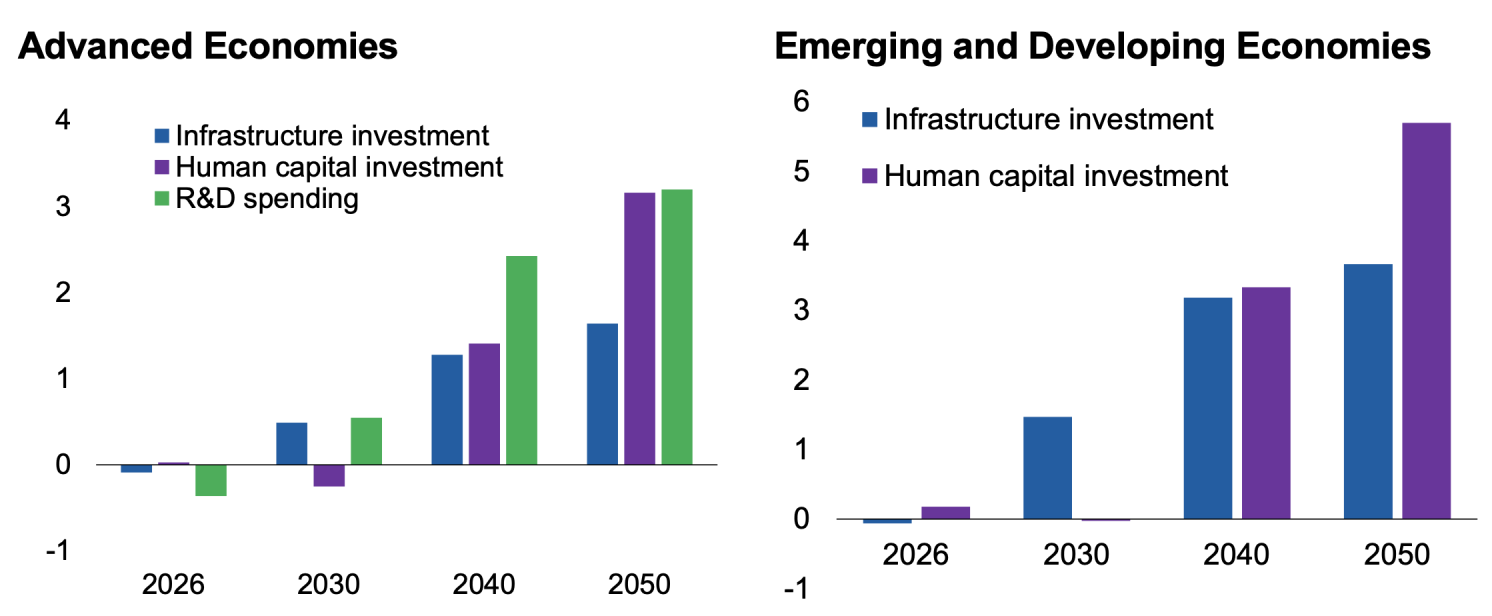

Figure 2 Long-term output gains from reallocating spending (percent)

Notes: The bars show long-term output gains due to a permanent increase, in the expenditure categories listed in the legend, of 1% of GDP in 2025, funded by a cut in public consumption.

The results show that reallocating 1% of GDP from government consumption (such as administrative overhead) to public investment in human capital – such as updating national curricula and equipping schools – can increase output by 3% in advanced economies and 6% in emerging market and developing economies over the long term (Figure 2). The larger gains for emerging market and developing economies reflect their lower initial levels of human capital, which implies a higher marginal return on investment. These findings are echoed by de La Maisonneuve et al. (2024), who highlight that boosting participation in early childhood education and increasing education spending among the lowest-spending countries could generate large gains in long-run productivity. The output gains emerge only after about 15 years, when the next generation enters the labour force.

Similar reallocations to infrastructure investment yield long-term output gains of 1.5% in advanced economies and 3.5% in emerging market and developing economies. In advanced economies, reallocating public spending toward R&D by 1% of GDP could boost output by 3% over the long term.

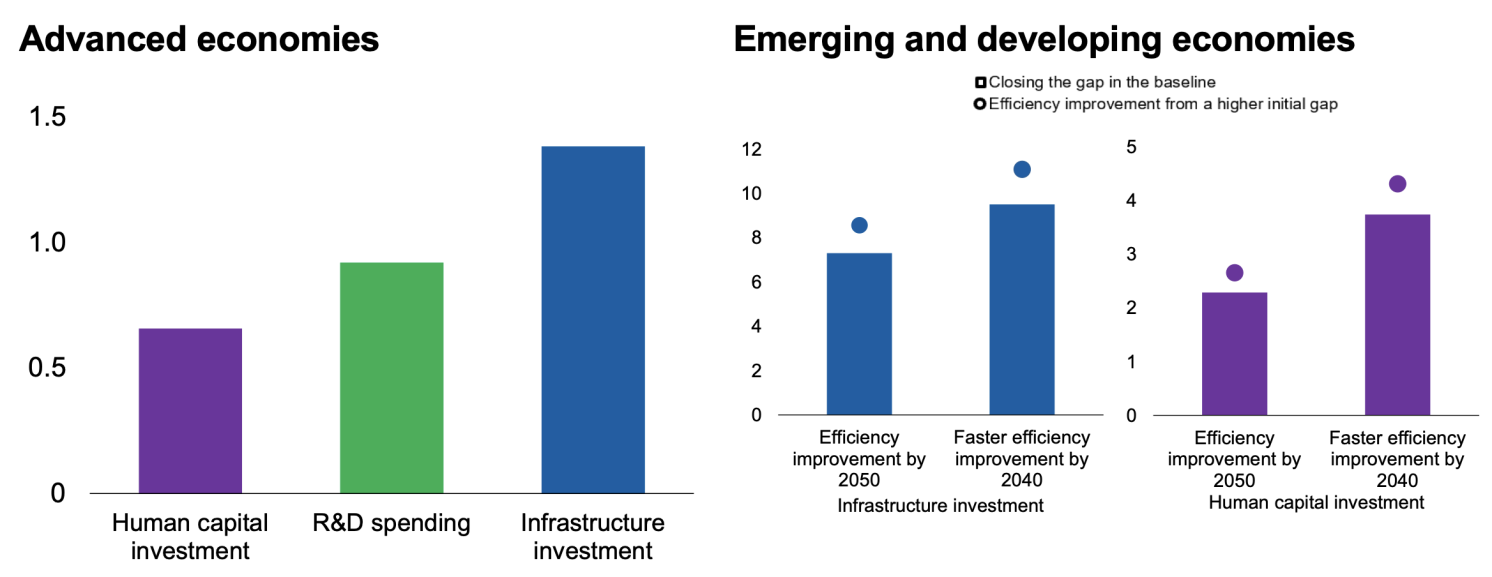

Crucially, closing gaps in spending efficiency can further increase the output impact by 1.5% in advanced economies and 2.5-7.5% in emerging market and developing economies, as more of the available public spending translates into productive forms of capital and scientific knowledge (Figure 3). The output gains can be up to 2% larger if spending efficiency is improved faster.

Complementary policies can further augment these gains. In advanced economies, combining investments in human capital and R&D yields greater benefits than focusing exclusively on one area, as innovation and skills complement each other. For emerging market and developing economies, pairing infrastructure and human capital investments capitalises on both short-term and long-term gains.

Figure 3 Long-term output gains from improving spending efficiency (percent)

Notes: The bars show the long-term output gains when gaps in spending efficiency are gradually closed, by 2050 in the left panel, and in the right panel, by 2040 or 2050 as indicated on the horizontal axis. In the right panel, the circles show the larger gain that is achievable for countries starting from a higher initial efficiency gap.

See original post for references