But markets do not stand still. Over time, some asset classes outperform while others lag. Stocks may surge ahead during a bull market. Bonds may stabilize the portfolio during downturns. As those returns compound at different rates, the asset mix begins to drift from your original allocations.

An 80% equity portfolio can quietly become 85% or 90% equities after a strong rally. A rough year for stocks can tilt you further into fixed income than you intended. Performance swings, good or bad, can push your portfolio away from the risk profile you originally chose.

At some point, the mix no longer reflects your original plan. So, should you step in and rebalance?

You might look to large ETF providers for guidance. The answers are not always clear. The Vanguard Growth ETF Portfolio (VGRO), for example, states that its 80% stock and 20% bond portfolio may be rebalanced at the discretion of the sub-advisor. That leaves plenty of room for interpretation.

Others are more prescriptive. The Hamilton Enhanced Mixed Asset ETF (MIX) uses 1.25x leverage on a 60% S&P 500, 20% Treasury, and 20% gold allocation. Hamilton specifies that it rebalances automatically if weights drift 2% from their targets. That is a tight band and implies frequent turnover.

But you are not running a fund with institutional constraints or leverage targets. You are managing your own portfolio. For most DIY investors, a simpler approach works better. Rather than reacting to every small market move, sticking to a consistent, time-based rebalancing schedule can reduce complexity and prevent decision fatigue.

In today’s column, we will look at why you should rebalance, how different time-based approaches have historically behaved, and why consistency often matters more than perfect timing.

Why rebalance your portfolio at all?

Rebalancing is the process of selling assets that have grown beyond their target weight and buying those that have fallen below it, such that you restore your portfolio to its intended allocation.

X

When you combine assets that are not perfectly correlated and periodically rebalance them back to target weights, you create what is referred to as a rebalancing premium. The underlying explanation has to do with how returns compound.

The arithmetic return is the simple average of yearly or periodic returns. It treats each period independently. The geometric return is the compounded growth rate of your money over time. It shows what you actually earn after gains and losses build on each other.

The arithmetic average of returns does not reflect the true investor experience. Investors live with the geometric return, which accounts for the effects of compounding and the impact of volatility.

Large swings in portfolio value widen the gap between arithmetic and geometric returns. By blending assets with different correlations and rebalancing them, overall volatility can be reduced. That narrows that gap and improves the compounding outcome. A simple back test illustrates this effect.

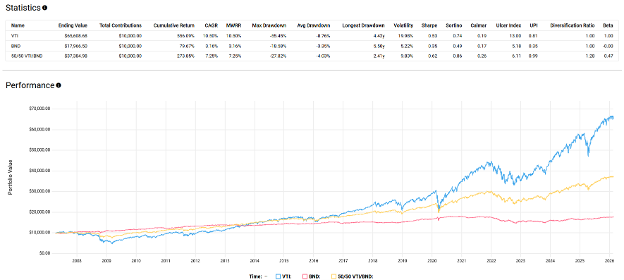

Source: testfolio.io

From April 2007 through February 2026, U.S. stocks returned 10.5% annualized. U.S. bonds returned 3.16% annualized. If you simply averaged those two numbers, you get 6.83%.

Now consider a portfolio that held 50% U.S. stocks and 50% U.S. bonds and rebalanced once per year. That portfolio returned 7.25% annualized over the same period. The difference between 7.25% and 6.83% of 0.42% per year reflects the benefit of combining and rebalancing the two asset classes rather than simply averaging their stand-alone returns.

The improvement also shows up in risk-adjusted terms. The all-stock portfolio delivered a Sharpe ratio of 0.53. Bonds delivered 0.35. The 50-50 portfolio, rebalanced annually, achieved a Sharpe ratio of 0.62. Even though its raw return was lower than 100% stocks, it generated more return per unit of risk taken.