The Bridgeman family’s strategic meetings initially began informally over meals, as Junior Bridgeman’s three children took more interest in his businesses and investments. Later, they turned into quarterly gatherings as “a Q&A for my siblings and I with our dad,” said Eden Bridgeman Sklenar, daughter of the former professional basketball player turned legendary billionaire investor.

Processing Content

As she and her two brothers learned Bridgeman’s restaurant franchise businesses from the ground up — much as their father once worked behind the counter at his early Wendy’s locations in the 1980s — over time the meetings shifted to a monthly schedule and a more exploratory tone around potential investments. Bridgeman Sklenar credited those sessions, along with teams of professionals that included financial advisors and her dad’s competitive drive (honed on the basketball court) to find a new edge, with the family’s pivot into the Coca-Cola bottling businesses that pushed its fortunes to new heights.

“We were meeting on a monthly basis for years, and, still, even in our father’s passing and absence, we still meet on that cadence, as we now were in full implementation,” said Bridgeman Sklenar, CEO of EBONY Media Group, which the family acquired in 2021. “A lot of things were theory, and now they are in full effect, as we even plan for the third generation, since my siblings and I are all proud parents and very much understanding the differences between generations and fortifying where wealth will be transferred as smoothly as possible to that next generation.”

READ MORE: How advisors can reduce estate planning conflicts in 4 steps

EBONY Media

At the ‘very, very, very top’

Those family meetings, and how Bridgeman paired learning with labor, offer lessons for both wealth management professionals and investors. So does the way he steadily built wealth from a base of $3 million that he earned over his solid 12-year National Basketball Association career as a sharpshooting sixth man primarily with the Milwaukee Bucks. He died last March at 71 years old of a cardiac event at a charity benefit after buying a stake in the Bucks and joining Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson and LeBron James as the only billionaire players in the history of the NBA.

In honor of Black History Month, Financial Planning is exploring Bridgeman’s legacy and accomplishments. He represents the polar opposite image of athletes or other people who come into sudden wealth from humble backgrounds spending away their earnings on luxury trappings or falling victim to bad actors. But he also paved a path for athletes of today. He secured free agency rights through his leadership of the National Basketball Players Association, gave his time and energy back to union and NBA financial education and professional services efforts dating back to their nascent days and displayed how to apply the knowledge he gained in and around the sport toward investing success and generational wealth.

That came from Bridgeman’s combination of drive, intellectual curiosity and close collaboration, his daughter said. She acknowledged, however, that the fact that her mother Doris and siblings Justin and Ryan have a “lot of harmony — my brothers and I are best friends” — make them the antithesis of the feuding wealthy families of popular culture and ugly legal fights.

“Every deal that our family has done has always been guided by various strategic financial advisors from the different banks and entities that we use for research knowledge,” Bridgeman Sklenar said. “Being a professional athlete that was part of a team, that is something that we still carry through, and we’re very fortunate that that team that surrounds the family are individuals that we’ve been working with for decades now, so that that also helps with a lot of understanding the complexities, understanding the nuances with working with families.”

Her father may have been “the most successful businessman that we have had coming out of the NBA,” according to Ron Klempner, a longtime lawyer with the NBPA who is its senior counsel of labor relations.

Klempner placed Bridgeman at the “very, very, very top of post-NBA success stories” alongside the likes of Johnson, onetime U.S. Sen. Bill Bradley and two former mayors, Dave Bing and Kevin Johnson. And Bridgeman’s post-NBA accomplishments include his tenure as the NBPA’s president during the end of his career and early years of retirement from 1985 to 1988.

In 1987, the players union filed an antitrust lawsuit that yielded a settlement with the owners — the “Bridgeman antitrust suit” and the “Bridgeman agreement” — granting veteran players the right to unrestricted free agency after their second NBA contract. In addition, the agreement delivered the first pension for players whose careers ended prior to 1965 and reduced the number of rounds in the NBA draft. The shift in free agency rules was “a complete game-changer” that is still in place today, Klempner said. Before, any teams that matched another team’s offer retained what was basically a right of first refusal against any outside bid.

“If you don’t have any say in where you can play relatively early in your career, then you’re really being very much hampered and restricted throughout your short career, so it’s very, very important what was done then,” Klempner said. “What Junior did opening up free agency is life-changing.”

READ MORE: Advisors clamor for estate planning tools as attorneys wave red flags

Tony Tomsic/Getty Images

From basketball to the business world

Remarkably, Bridgeman was leading that monumental shift for NBA players just as he was first laying the groundwork for his family’s fortune.

Shortly after retiring from the NBA, he and a business partner bought five Wendy’s franchises in and around Milwaukee, he told The New York Times in 2004. Some earlier attempts to wade into the business were unsuccessful, but Bridgeman had been thinking about how to invest in food franchises for around a decade. This time he would prove his view that, in his words, “One of the great misconceptions about ownership is that you just sit back and let others do all the work.” He was filling the fast food orders, running the register and cleaning the bathrooms to the point that local Bucks fans thought he was struggling financially, Bridgeman often recalled over the years. But he was executing his long-term investment strategy.

”I felt that one thing people were always going to do was eat,” Bridgeman told the Times. ”So since I was looking to invest in something, I figured food would be the safest investment.”

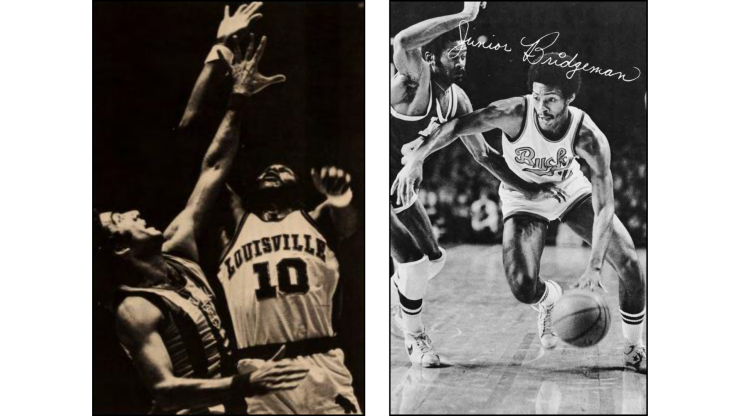

The son of a steelworker from East Chicago, Indiana, Ulysses Lee Bridgeman Jr. had starred in in high school with the state champion Washington High School Senators and in college as an All-American with a 1975 Final Four appearance as a member of the University of Louisville Cardinals. He graduated that year with a bachelor’s degree in psychology. The Los Angeles Lakers picked him as the eighth overall pick in the 1975 draft before trading him to the Bucks in the deal that sent Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to L.A. Alongside Bucks teammates like Sidney Moncrief, Marques Johnson and Bob Lanier, Bridgeman brought instant offense from the bench as a 6-foot-5 small forward and shooting guard with a career average of 13.6 points per game. He played 849 of them in the NBA between his time in Milwaukee, where the Bucks retired his No. 2 jersey at the end of his playing days, and a two-year stint with the L.A. Clippers.

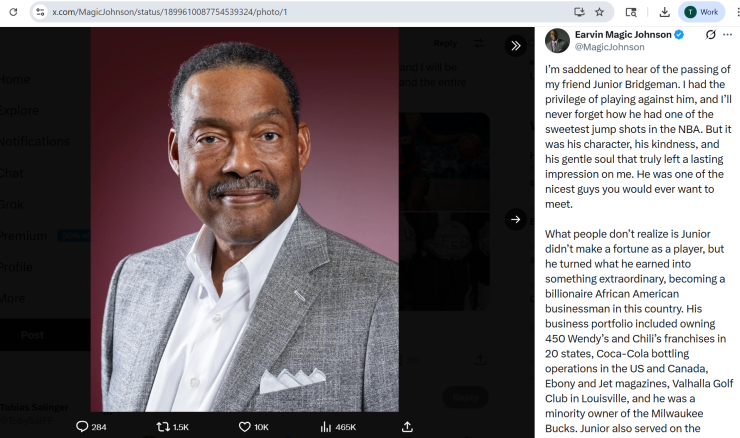

Magic Johnson’s statement upon Bridgeman’s death last year recalled how he “had one of the sweetest jump shots in the NBA.” On the other hand, Johnson’s tribute and so many others focused primarily on what Bridgeman accomplished after his career. Those eulogies came from the Bucks, current and former players, politicians like Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg and Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky and officials like NBA Commissioner Adam Silver and Louisville President Kim Schatzel. Johnson recalled how the fundraiser benefits and parties that Doris and Junior Bridgeman held each year at the Kentucky Derby created spaces there for Black Americans “that had historically been out of reach for many in our community.”

“What people don’t realize is Junior didn’t make a fortune as a player, but he turned what he earned into something extraordinary, becoming a billionaire African American businessman in this country,” Johnson wrote. “You spent so much of your post-playing career mentoring and educating athletes and I always reference your journey when I speak to young athletes about transitioning from the court or field to the boardroom. Your legacy will transcend beyond your financial success to the doors you opened for so many and inspiring generations to come.”

READ MORE: Legendary role models whose achievements laid the foundation

Johnny Nunez/Getty Images for EBONY Media

Carrying the legacy forward

Bridgeman was survived by Doris, his college sweetheart and wife of five decades; Bridgeman Sklenar of EBONY; Ryan, who is president of Manna, which operates the family’s hundreds of restaurant franchises; and Justin, the CEO of Heartland Coca-Cola Bottling Company, a distribution network spanning tens of millions of cans and bottles a year. All told, taking into account the 2021 deal that brought EBONY and JET magazines’ parent company out of bankruptcy protection and including the restaurant and Coke bottling businesses, the 10% share of the Bucks that Bridgeman acquired in 2024 and the 25% stake the longtime member of Louisville’s Valhalla Golf Club purchased in 2022, Forbes magazine estimated Bridgeman’s net worth last year at $1.4 billion.

But the numbers fail to capture some of the characteristics that those closest to him said made that success possible. For example, his EBONY obituary noted his “deep Christian faith” and membership in Louisville’s Southeast Christian Church, as well as the fact that the Manna brand name symbolized “his unwavering belief in God and foundational dedication to integrity, generosity and service.” The investment in EBONY came out of a larger mission, as well.

“When you look at EBONY, you look at the history not just for Black people, but of the United States,” Bridgeman once said. “I think it’s something that a generation is missing, and we want to bring that back as much as we can.”

Bridgeman Sklenar, who was previously chief marketing officer of Manna, has led EBONY’s shift under the tagline “Moving Black Forward” from the EBONY and JET print magazines to digital media to events such as its Power 100 list and an 80th anniversary celebration last November.

The opportunity “to start with incredible IP” as a pillar of Black-owned media and African American culture and “being able to reimagine and apply a lot of the legacy, but creating future-forward business,” attracted the family as a profitable venture, she noted. The investment presented the prospect of doing “what we hope all of our businesses have done, which is create a version of wealth creation for all the employees that work for us,” Bridgeman Sklenar said. At the same time, her family was aiming to preserve EBONY.

“We live in very interesting times in media, so using the principles that our family stands for, the values that we stand for, and being able to bring that forward as a guiding light in a time when so much is being suppressed and truth being much harder to point out, we wanted to ensure that EBONY could be that legacy voice, while also creating a viable and sustainable business,” she said.

READ MORE: Keeping the kids: An advisor’s guide to retaining next-gen clients

Financial advisors’ reflections

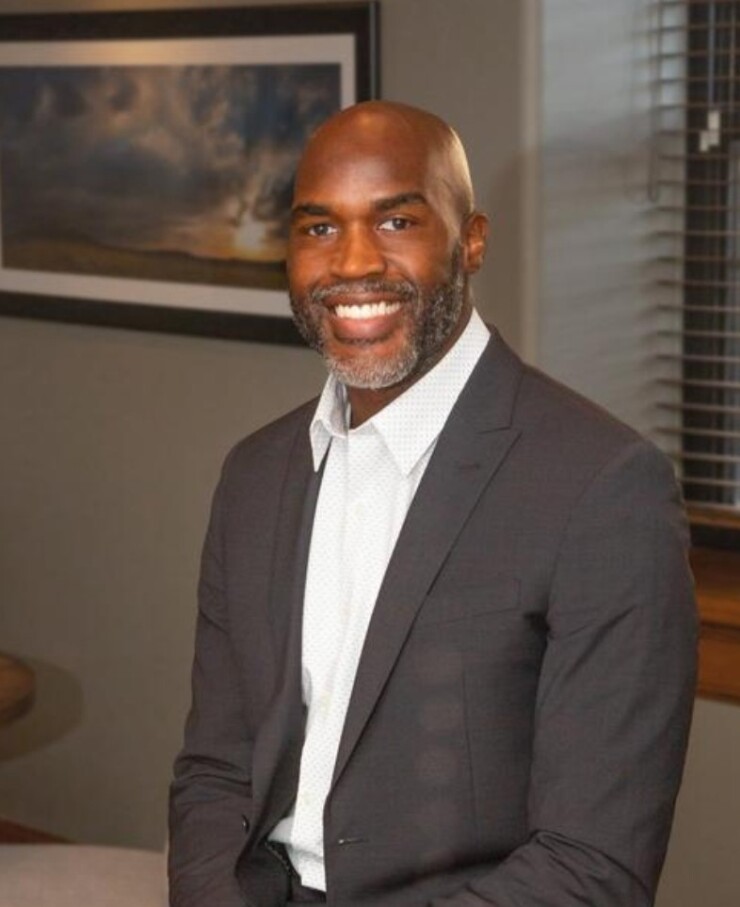

The news of the EBONY investment first brought Bridgeman to the attention of Pat Brown, a wealth manager in the Lawrence, Kansas-based office of Creative Planning, the founder of an organization called Financial Literacy for Student Athletes and author of several books aimed at educating young people and their families about building wealth. He’s also a former all-conference linebacker with the University of Kansas Jayhawks football team.

Pat Brown

For Brown, Bridgeman’s story signals to young people how an athlete can apply “that same regimen” of training, nutrition and peak performance to long-term investments. It also shows that the more basic types of tactics, such as, say, opening a Roth individual retirement account or a vehicle that sounds more like “some paint drying on the wall type of investment” pay off more over time than some flashy deal, he said.

“You can’t just throw a little money at it and then walk away,” Brown said. “The stuff that you may see on TV is not necessarily realistic.”

And a growing number of athletes are adapting to that ownership approach these days, whether it’s the investments of retired greats like Johnson and Jordan, current stars like James and Kevin Durant or even college standouts like JuJu Watkins, the University of Southern California Trojans basketball player who bought into a professional women’s soccer team last year.

Bridgeman “didn’t use basketball to look rich, he used it to actually be wealthy,” said Nisiar Smith, founder of Philadelphia-area Courtside Wealth Partners, where pro basketball players and other athletes are his main client base. The salaries of never more than $350,000 per year acted “as seed capital and not the finish line,” Smith said, describing Bridgeman’s approach as one of “consistent execution over decades” with strong systems and predictable demand.

Nisiar Smith

“Your contract isn’t viewed as, ‘You-made-it money.’ It’s, ‘I have money that I can build upon,'” Smith said. “Him investing in the ownership mindset helped create equity cash flow and scale for himself and his family. … Endorsements pay once; ownership pays every year.”

READ MORE: How business owners’ exit plans create big openings for advisors

Paying it forward

Leaders of regional banking giant Fifth Third Bank, where Bridgeman was a member of the company’s national board for almost a decade starting in 2007, after a tenure of more than nine years on the Louisville branch’s board, also paid their respect and admiration after his passing. (Bridgeman had other board tenures with Churchill Downs Racetrack, the trustees of the University of Louisville, the WHAS Crusade for Children and Jackson Hewitt.)

“Junior was kind, approachable, patient and always willing to help,” Kevin Lavender, the vice chair of Fifth Third’s Commercial Bank, said in a statement to FP. “He was the epitome of a successful businessperson, someone who understood that true success isn’t measured only in returns, but in the opportunity you create for others.”

Bridgeman “showed us what it looks like when business success is paired with humility, generosity and a genuine love for the community,” Fifth Third Bank Kentucky Regional President Kim Halbauer added. “Junior wrote the playbook on how generational wealth is not just financial strength, but shared values, shared purpose and shared responsibility to lift others.”

That playbook was a long time in the making. Bridgeman had been learning about investing at least as far back as his early days in the NBA through his lifelong reading habit and observing people like Wayne Embry, a retired player, the Bucks general manager and a McDonald’s franchisee, and Bucks owner Jim Fitzgerald, he told ESPN in a 2024 profile. He set a goal of saving $1 million during his career. In 1978, he committed to investing $150,000 over a few years as part of a group led by Fitzgerald in purchasing a cable TV business. When Fitzgerald sold off that business about five years later, Bridgeman’s investment generated a profit of $550,000.

During those early days, Bridgeman first became a players’ representative to the NBPA and helped spur the union to reach out to investment firms in 1981 in order to arrange for executives to speak with members about financial literacy. After his retirement, he led an NBPA program designed to teach players the restaurant business in the early ’90s and spoke to about 60 rookies each year in the latter part of that decade as part of the league’s Rookie Transition Program. Over time, those early efforts have blossomed into current resources like the Business Mentorship Program, a 10-week mentorship centered on a player’s business interest, professional services like auditing and forensic accounting to detect red flags and databases that players can use to examine any financial professional’s background.

READ MORE: How this RIA jumped two succession hurdles at once

1974 Déjà Vu Yearbook, University of Louisville Archives; Milwaukee Bucks 1976-1977 Official Press Radio-TV Guide

Ownership, from the ground up

Bridgeman was always sharing what he had learned and earned with others. He had moved into the restaurant business in 1984 with a passive minority stake in a Chicago Wendy’s location, but his first majority ownership in a franchise in Brooklyn in 1987 with fellow former NBA player Paul Silas proved a failure. So Bridgeman embarked on a training program for Wendy’s franchise owners that took him on a tour of other franchises to glean what made them successful. He invested roughly $750,000 in five Milwaukee-area locations alongside a business partner in the venture.

“He’d be working in the restaurant like he was an hourly worker,” Moncrief, his former Bucks teammate, told ESPN. “I witnessed that. I was thinking, ‘What the heck is he doing in there flipping burgers, washing dishes?’ And he had those work pants on. But he understood the value of learning thoroughly what you’re investing in — very, very hands on.”

X

That hard work and dedication paid off. Within two years, the Wendy’s locations’ annual revenue had jumped to $2 million each from only $600,000. Then he picked up 16 more locations in Milwaukee and bought outposts in Madison, Wisconsin, then in Louisville, Nashville, Tennessee and Florida. Bridgeman eventually expanded his franchise’s footprints into an empire that would grow to 525 restaurants across locations of Wendy’s, Pizza Hut, Chili’s, Fazoli’s and Blaze Pizza, where James was a co-investor as well. His children learned the inner workings of the businesses, Bridgeman Sklenar noted, recalling her time operating the Wendy’s grill, drive-through and register under the tutelage of her father and mother.

“My brother Ryan and I, we say we got a promotion when we were able to work in the actual office, but we started out as the janitorial crew,” Bridgeman Sklenar said. “You had to understand all corners of the business. If you were going to be in ownership, you had to understand the complexities and all that it takes to run a business. And you were going to understand every position that you possibly could, and their level of importance.”

The family still owns many franchise businesses through Manna. In a 2024 interview with the Franchise Times, her older brother Ryan similarly compared the family’s current stable of more than 230 locations of Wendy’s, Fazoli’s and Golden Corral to running a team race in track and field.

“You’re constantly passing things off to the next guy and those handoffs are going to determine your success,” he told the publication.

READ MORE: 12 tips for financial advisors on working with athletes and entertainers

Newer holdings, generational wealth

The Bridgemans had pared back their restaurant holdings with a deal spinning off several hundred of the locations in 2016. Then they secured a second transaction that year out of their existing relationship with Coke through those franchises and a “strategic plan of being able to get in with Coca-Cola at the right time, right place,” Bridgeman Sklenar noted.

The soda company was consolidating other independent bottlers under its ownership in those years. The family sold the restaurant franchises for $250 million and later acquired Heartland Coca-Cola for $290 million, according to estimates by Forbes. After the expansion of that business, the magazine said that Heartland was generating nearly $1 billion in annual revenue by last year. The 2016 deal to buy Heartland and another transaction two years later gaining a minority stake in Coke’s Canadian bottling operation alongside Toronto Raptors and Maple Leafs owner Larry Tanenbaum brought diversification.

X

Those newer holdings also spoke to her father’s desire for “successful multigenerational wealth” and a “touch of that competitiveness that would have driven him through his professional basketball career,” Bridgeman Sklenar said. “A lot of individuals would say, ‘OK, I’ve had success here, and I’m just going to ride this into the sunset,’ versus for our father, it was always, ‘OK, well, what’s my next challenge? What can I do to stretch my ability and grow and learn?'”

In a 2022 article, The Athletic calculated that his initial investment in the Wendy’s locations in Milwaukee had effectively grown by a factor of 667.

By then, current NBA players were “realizing that now we have the assets to get involved in things that maybe guys from my time only dreamed about,” he told the publication. “Now, you really start to change what generational wealth really is all about. Yeah, they’ll make enough money where they’ll be in that category of being able to supply wealth for their kids and grandkids and on and on, but I’m talking about, you know, owning a significant, multibillion-dollar company that will go on and on, but, even more importantly, can influence what goes on in this country.”