The Federal Reserve is set to lower the target policy interest rate this week in spite of the fact that price inflation rose again in August. The Fed has, for many years, insisted that it is equally committed to both sides of its so-called “dual mandate” of pursuing both “price stability” and maximum employment. Yet, the Fed is increasingly showing that price inflation is not even one of the central bank’s chief concerns. If the Fed cuts the target federal funds rate on Wednesday, we will know that what really matters for the Fed is not price inflation. What really concerns the Fed is ensuring the Treasury has access to cheap credit while attempting to help the administration politically by temporarily driving up employment numbers with ever higher levels of monetary inflation.

CPI Inflation Rose in August

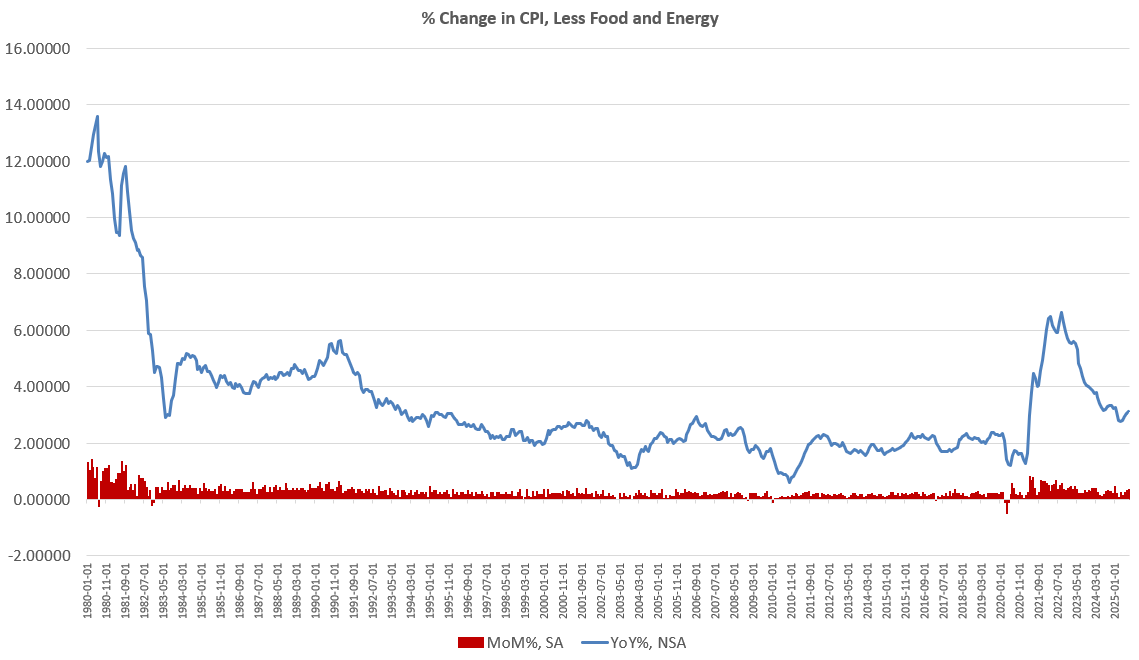

According to the latest consumer price index (CPI) report from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the CPI rose in August by 2.9 percent, year over year. That’s an eight-month high. During July of this year, the CPI year-over-year increase was 2.7 percent. When compared month over month, the CPI rose in August by 0.38 percent, which was also an eight-month high. Month over month, CPI inflation rose in July by 0.19 percent.

In other words, price inflation accelerated during August, coming in at the highest rates since January of this year.

Looking to core CPI inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, the situation was no better. Year over year, the CPI rose by 3.1 percent, a seven-month high, and above July’s increase of 3.05 percent. Month over month, the CPI rose in August by 0.34 percent, an eight-month high. This put core CPI even further from the Fed’s arbitrary target of two percent.

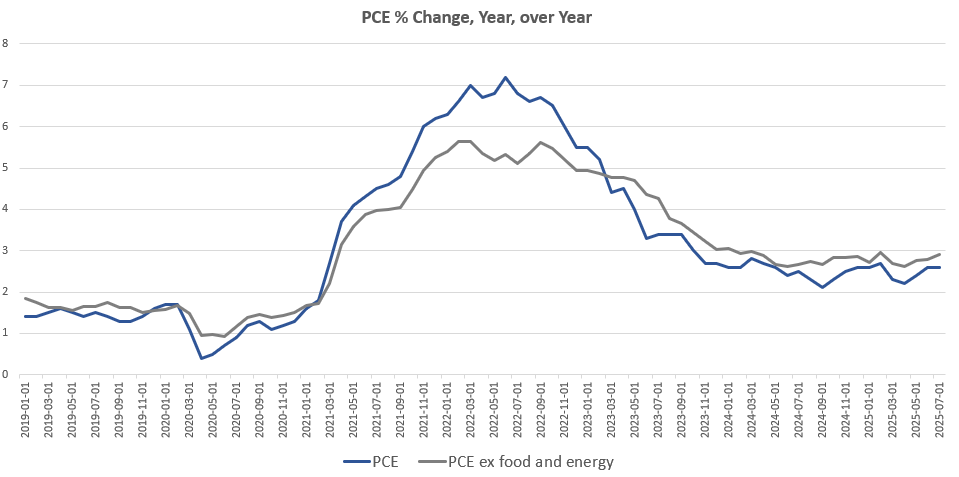

The latest CPI numbers also reflect the trend in the Fed’s preferred inflation measure: personal consumer expenditures (PCE). August data is not yet available for PCE, but July’s PCE report showed the PCE growing by 2.6 percent, year over year. The core PCE was no better with a July reading of 2.9 percent, which had accelerated above June’s core PCE growth rate of 2.8 percent.

Why has price inflation been so sticky following 2022-3, which saw 40-year highs in price inflation? Part of the reason is the Fed turned dovish long before price inflation had returned to the Fed’s two-percent target. Last fall, in the waning days of the 2020 presidential election, the Fed began a series of new cuts to the federal funds rate in September, while claiming that the US labor market was “solid.” It was widely suspected that the interest-rate cut was being done for political reasons, to facilitate economic stimulus to help the incumbent political party win re-election. To counter these accusations, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell claimed that price inflation was quickly returning to the two-percent target, and the Fed could cut interest rates without any danger of reigniting inflation. The Fed was clearly wrong. A year later, core CPI inflation is higher now than it was when Powell declared victory over price inflation.

The Fed Has Never Been Focused on Combatting Price Inflation

Regular readers of mises.org already know, of course, that the central bank is not now, and has never been, actually committed to controlling price inflation. Adter all, the central bank was created to facilitate monetary inflation, and that inevitably leads to price inflation, sooner or later.

In the present context, if the central were committed to reducing price inflation, it would, at the very least, stop using monetary inflation to purchase assets. Since 2008, for example, the Fed has purchased more than five trillion dollars in mortgage-backed securities and Treasurys. The Fed did this with newly “printed” money meaning that these asset purchases have, since 2008, created nearly one-fourth of the entire current money supply. This has translated into much of the price inflation that is presently making life unaffordable for so many Americans. The Fed does this to ensure ongoing asset-price inflation for wealthy asset owners and the Fed’s Wall Street allies.

The Fed’s cut to the federal funds rate last fall, which was obviously politically motivated, was another glimpse into one of the Fed’s true priority: using monetary stimulus to favor the ruling regime.

So, it’s safe to say that the central bank is certainly not committed in principle to combatting price inflation. However, if the Fed again cuts its policy interest rate this week, the Fed will be abandoning even its performative opposition to price inflation in which the Fed claims to be “committed” to returning price inflation to its two-percent goal.

Not only is consumer price inflation accelerating well above two percent in the August report, according to the federal government’s own data, but asset prices also continue to surge. As one observer on X/Twitter noted last week, asset prices remain robust with home prices, gold, bitcoin, and the S&P 500 all near all time highs. Yet the Fed will likely opt for more monetary inflation at its Wednesday meeting.

Part of the Fed’s ongoing lack of attention to its alleged two-percent target is due to significant pressure from the administration and from financial-sector activists who believe that an additional rate cut will further fuel asset price inflation and more employment. For example, on Wednesday, Donald Trump declared that there was “No Inflation!!!“—by which he meant price inflation—and demanded another Fed rate cut. (Trump didn’t have as much to say in response to Thursday’s CPI report showing rising price inflation.)

What Powell and the Fed Will Say

If Trump and Wall Street are successful in getting their demanded rate cut on Wednesday, we can expect more monetary inflation and more upward pressure on prices.

If the Fed cuts the target rate, Powell will have to come up with an explanation for why the Fed is embracing more easy money even as the price inflation rate is moving back up near three percent. Powell’s stated rationale will be that the Fed is willing to risk some additional price inflation if that’s what’s “necessary” to keep the economic boom going. Moreover, Powell and the Fed will maintain that if the economy is weakening, then this will lessen “inflationary pressures” overall and price inflation will go down in any case.

If only it were that easy.

First, attempting to stimulate job growth with more easy money won’t actually produce economic strength. Real economic strength comes from saving and investment. On the other hand, more monetary stimulus will, at best, merely create the illusion of increasing demand as consumers and buyers of assets bid up prices with the extra money that is now sloshing around in the economy. Employers will misinterpret rising prices as economic strength and then hire more workers. Unless the central bank injects even more monetary stimulus—and does it repeatedly—it will soon become apparent that there is no economic strength backing up the easy-money fueled temporary demand.

So, why not just keep adding more monetary stimulus over and over to keep the economy going? If monetary stimulus actually works to create jobs, why stop doing?

The answer of course is that monetary stimulus results on rising prices for both assets and consumer prices. We’ve been living with asset price inflation for many years at this point, and it’s why for-sale houses have generally become unaffordable for first-time homebuyers while the average age of homeowners has been rapidly increasing. Moreover, monetary inflation in recent years produced the 40-year highs in price inflation we’ve endured in recent years, with purchasing power falling by nearly 25 percent in just five years. This has been especially devastating for ordinary savers, those on fixed incomes, and those who don’t already own assets.

In other words, a policy of endless employment stimulus via monetary inflation is a policy of mounting price inflation and a falling standard of living.

The only solution to this—and the only way to allow ordinary people to regain some of their purchasing power—is to reject more easy money and to allow deflation to occur. Deflation would also help to unravel 20-plus years of easy-money fueled malinvestment and financial bubbles. Were this to occur, the economy would then be rebuilt along more sustainable lines that conform to actual market demand, in contrast to the easy-money economy of speculative manias that enriches wealthy asset-holders at the expense of ordinary people.

Unfortunately, we are unlikely to see much actual deflation, although it is badly needed.

Instead, the central bank will continue to force down interest rates as part of its easy money agenda. This is the opposite of what the central bank should do, which is to refrain from any further intervention in the economy. The Fed should stop buying assets of any kind, and allow interest rates to be set by the marketplace instead of by central planners at the Treasury and at the Fed.

As a result, asset prices would fall substantially, and the prices would rapidly become more affordable. It would also become possible again for ordinary people to earn a decent amount of interest on ordinary savings as interest rates gradually rose. In other words, the economy would—for the first time in decades—begin to swing back in favor or ordinary savers, young workers, and first-time home buyers.

Financing Federal Deficits: The Hidden Agenda Behind It All

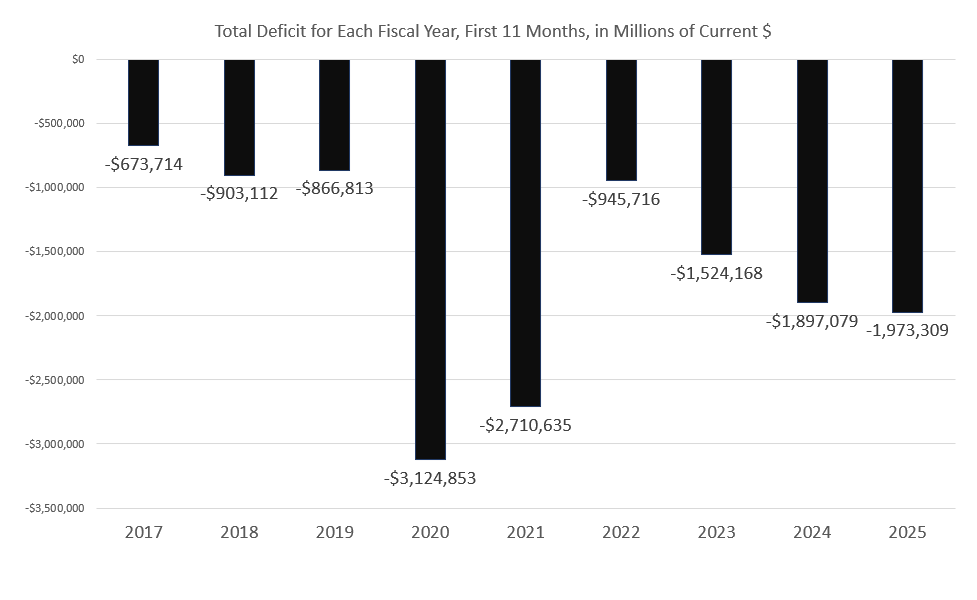

There’s another reason why the central bank won’t allow deflation and won’t allow interest rates to rise significantly. Although the Fed never publicly admits this, a central purpose of the Federal Reserve—and every other central bank—is to facilitate cheap borrowing for the government. As we saw last week, deficit spending in the United States continues to mount while the total size of the the federal debt speeds toward 40 trillion dollars. Moreover, the US Treasury this year faces a challenge of refinancing more than $9 trillion in US debt during the next year. With Treasury yields now at much higher levels than they were in recent years, refinancing at current interest rates will add a enormous amount of new interest expense to for the federal government, as the dept-to-GDP ratio continues to climb to 120%. The administration really wants to see the Fed force short term yields back down to ease the expense of massive federal deficits.

The regime in Washington now faces a double threat: a worsening employment situation and a worsening fiscal situation. Washington thinks that the best way to address this is through even more easy money. Get ready for the Fed to embrace a new cycle of monetary inflation soon.